The solution

Thanks to the Energy Technologies Institute (ETI) funded three-year research programme back in 2014, this challenge for increased capability of marine robotics has been attained. The project was delivered by a consortium of experienced companies including Fugro, National Oceanography Centre (NOC), British Geological Survey (BGS), Plymouth Marine Laboratory (PML) and ourselves, Sonardyne.

Along with increasing the capability of marine robotics for successful CO2 storage, four key technology elements for large carbon storage and monitoring projects were identified.

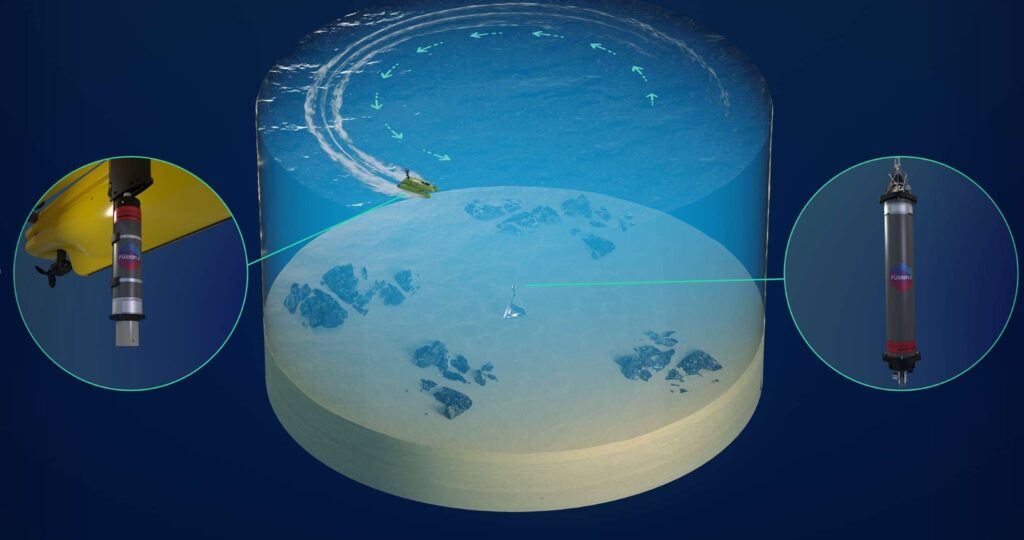

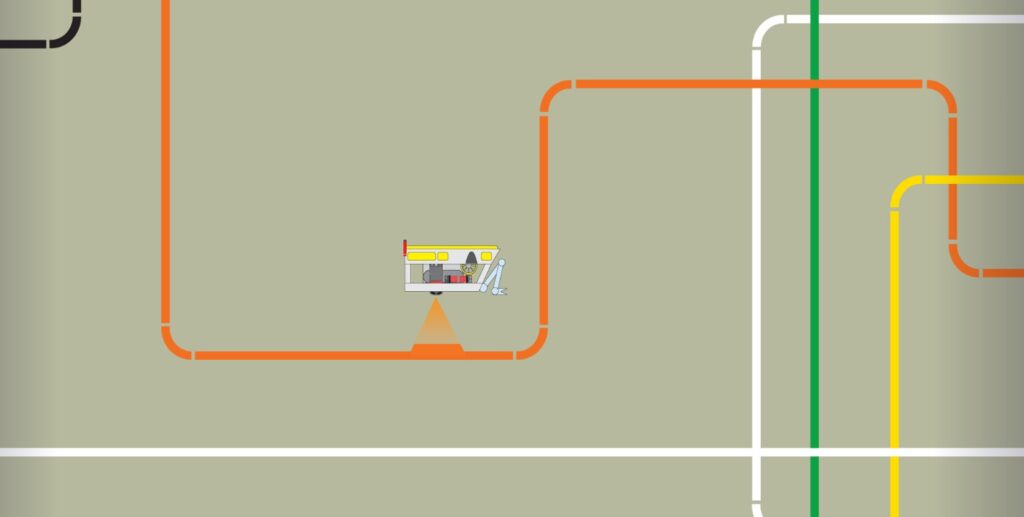

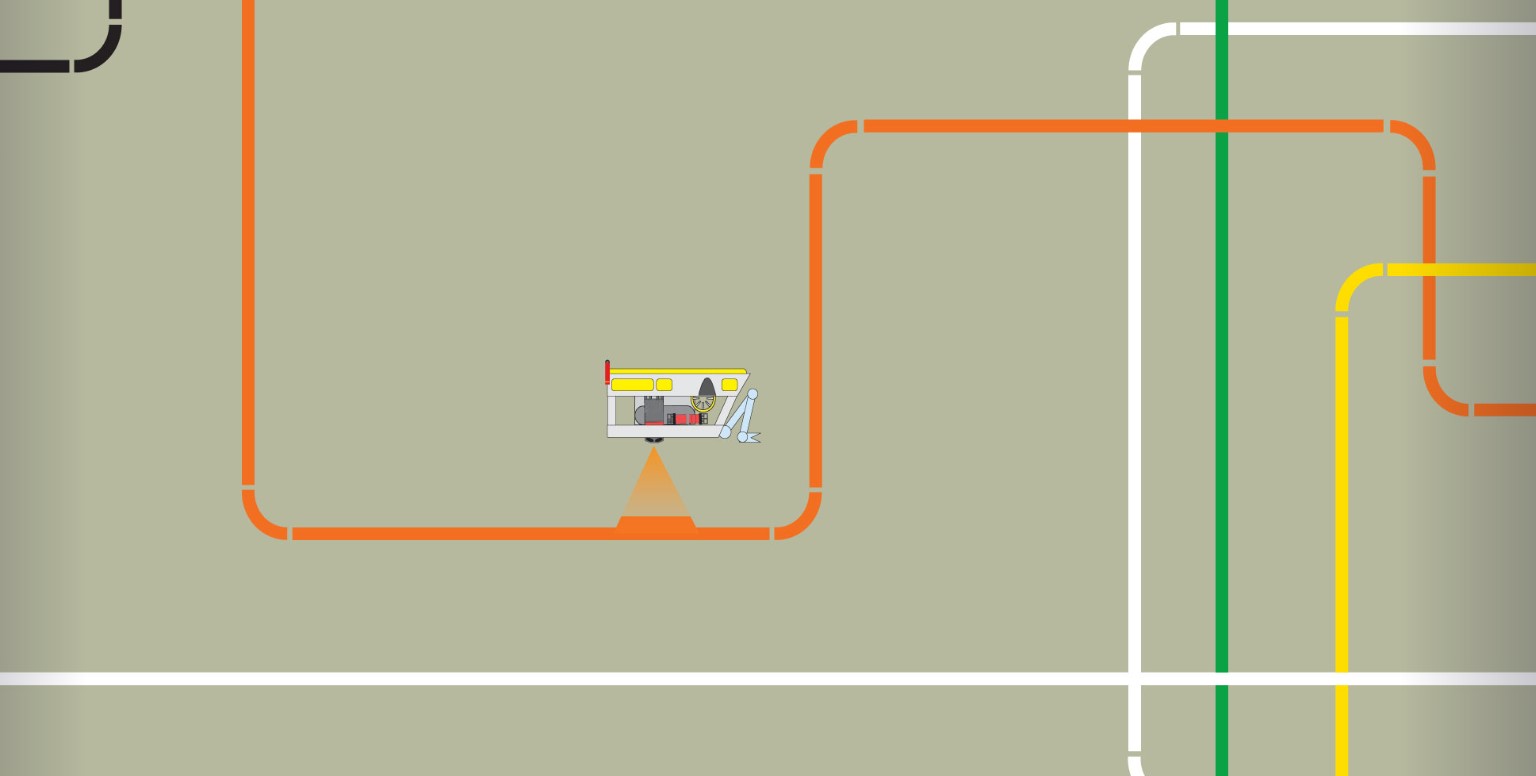

The first is a low-power and hence long-endurance autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV). This is required for cost-effective wide-area coverage surveys during baseline and repeat environmental surveys. We found using a combination of our Solstice side scan sonar and chemical sensing worked extremely well.

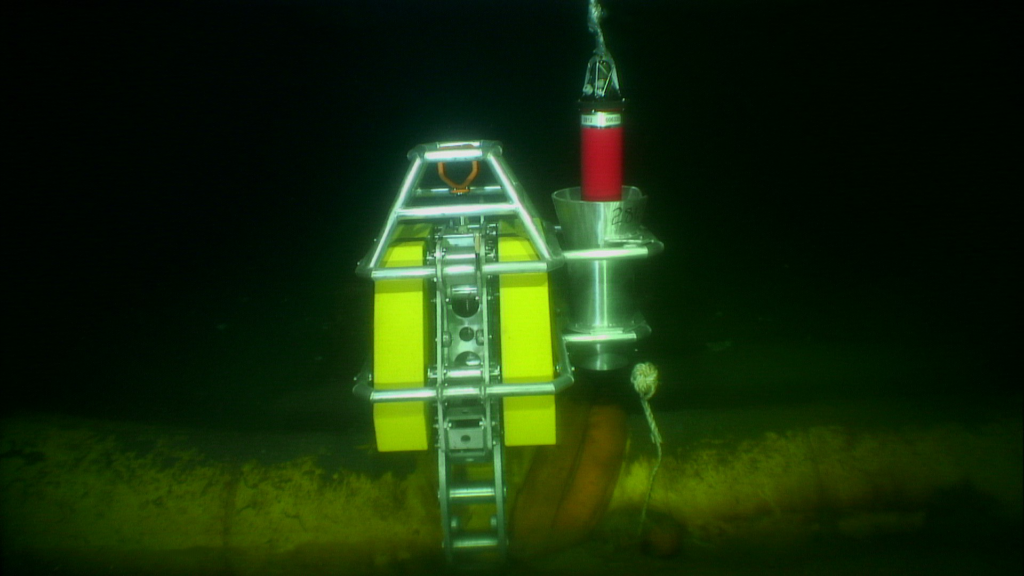

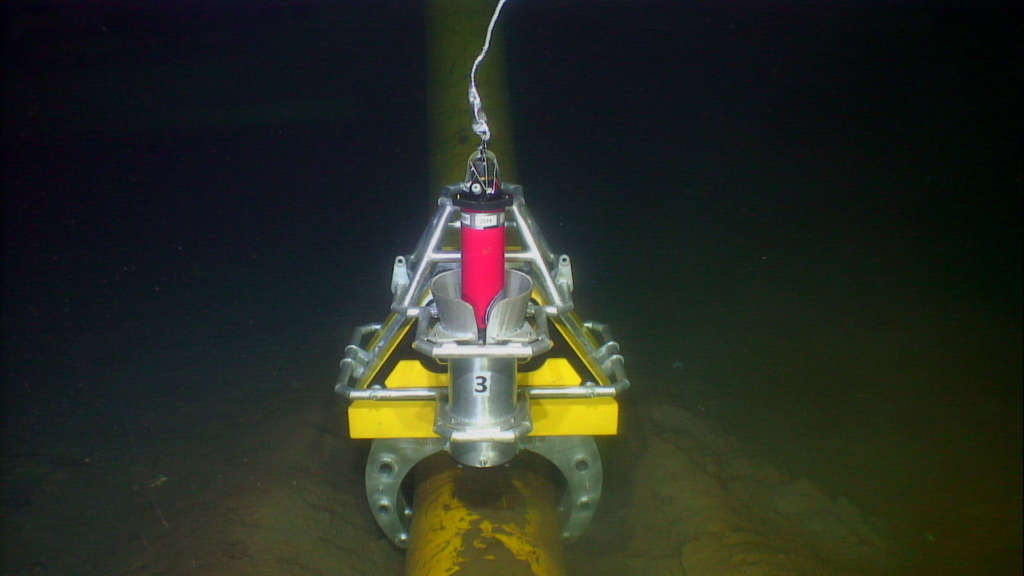

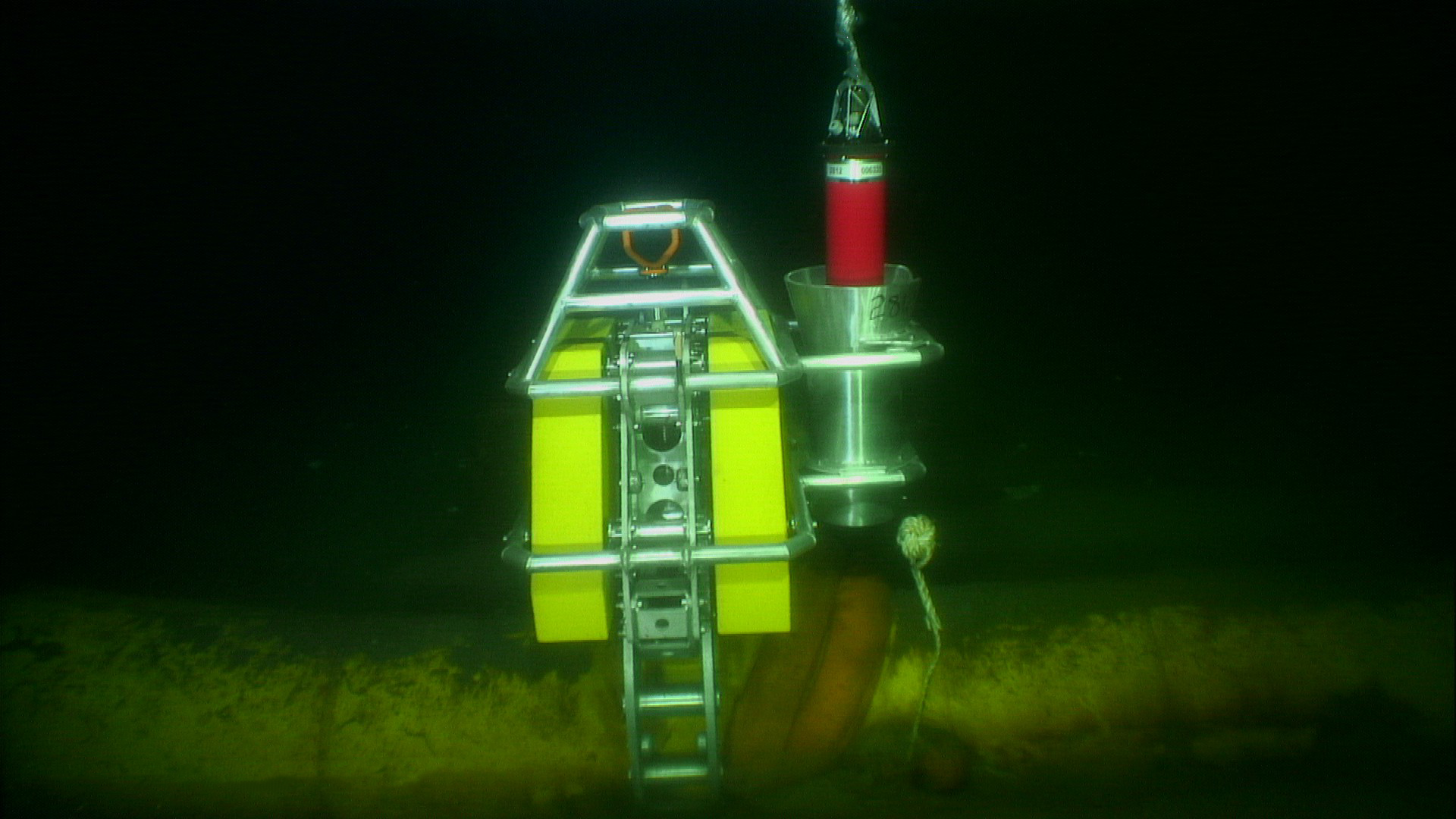

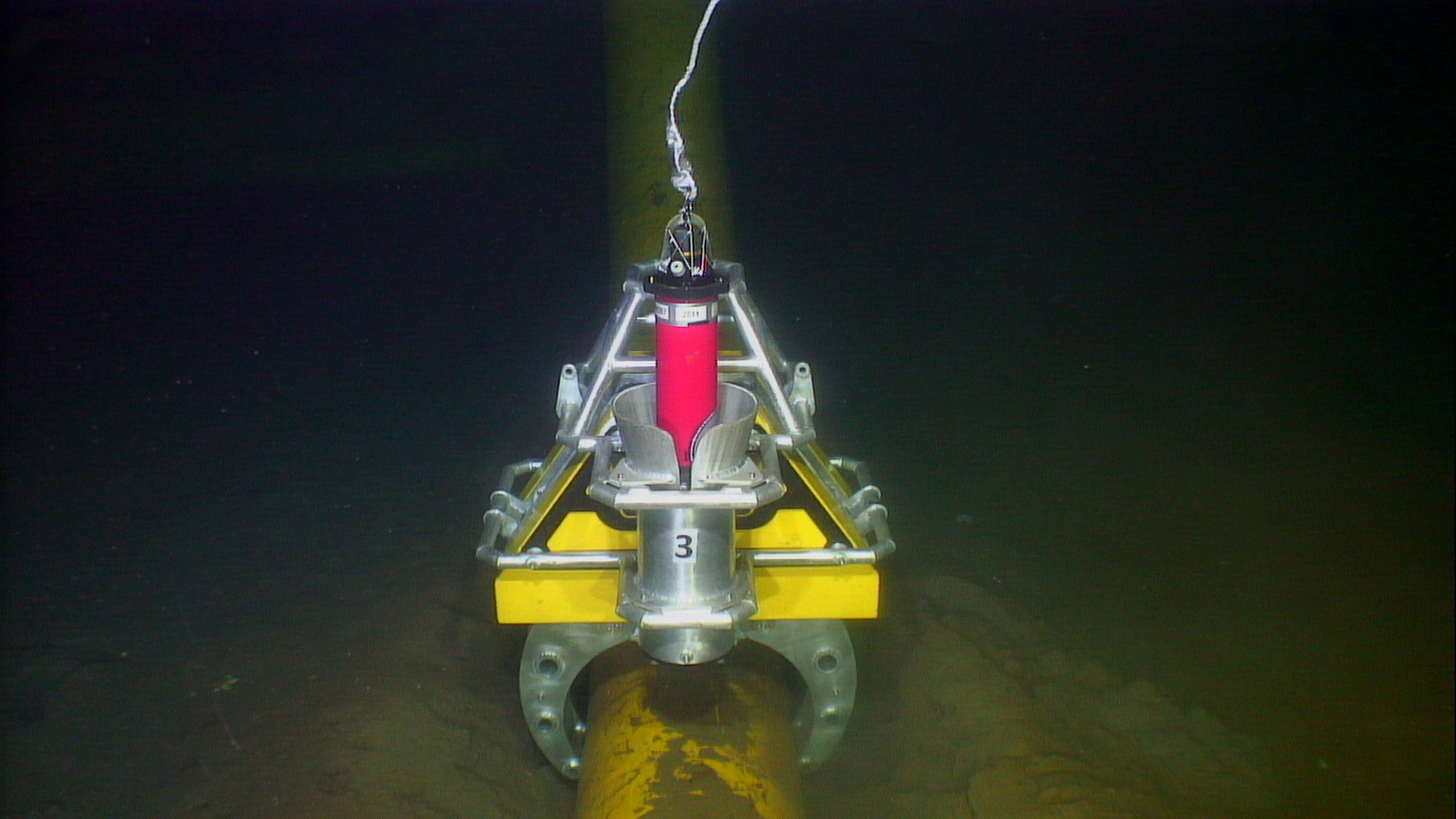

Second and third elements are seabed landers capable of detecting and monitoring any leakage at high-risk locations. These consist of two different landers, one using an active sonar and the second combining passive sonar and chemical sensing.

The active sonar lander, based on our Sentry integrity monitoring system (IMS), gives sensitive and reliable automated leak detection capability across a wide area. For instance, around an injection well, Sentry can monitor an area of over 2.3 million square metres, to help visualise that’s equivalent to around 325 football pitches. The passive sonar and chemical lander, uses the smarts from our underwater acoustics capabilities. It’s capable of both detection of leaks, but offers improved verification and has the potential to estimate leak rates at shorter ranges.

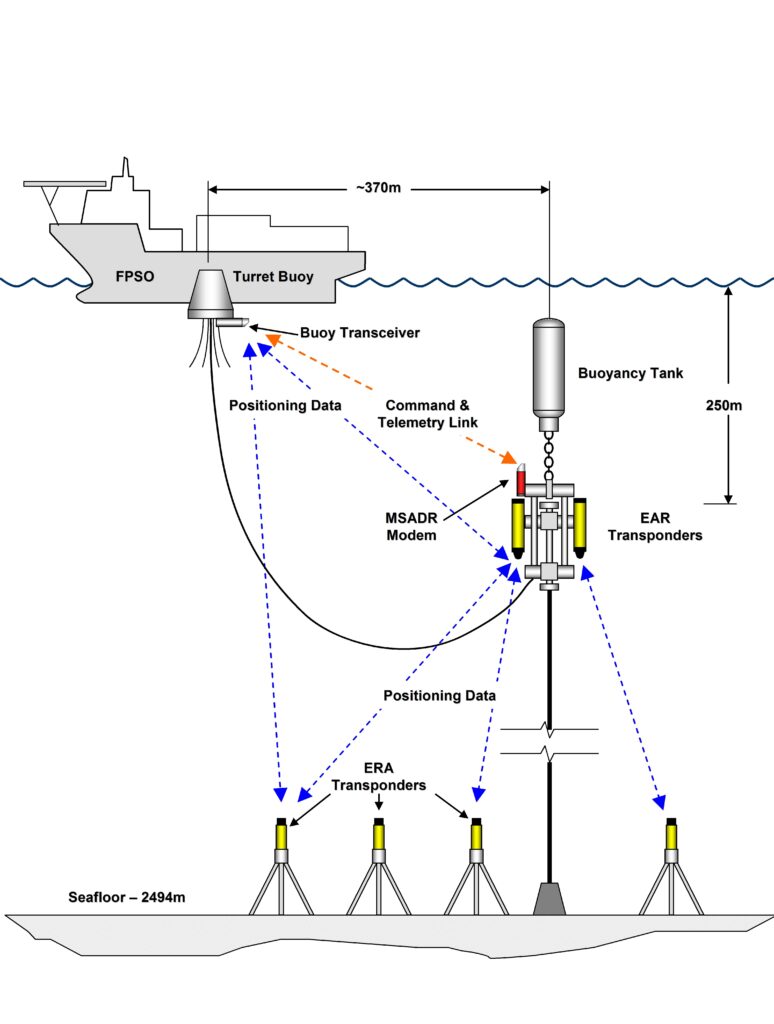

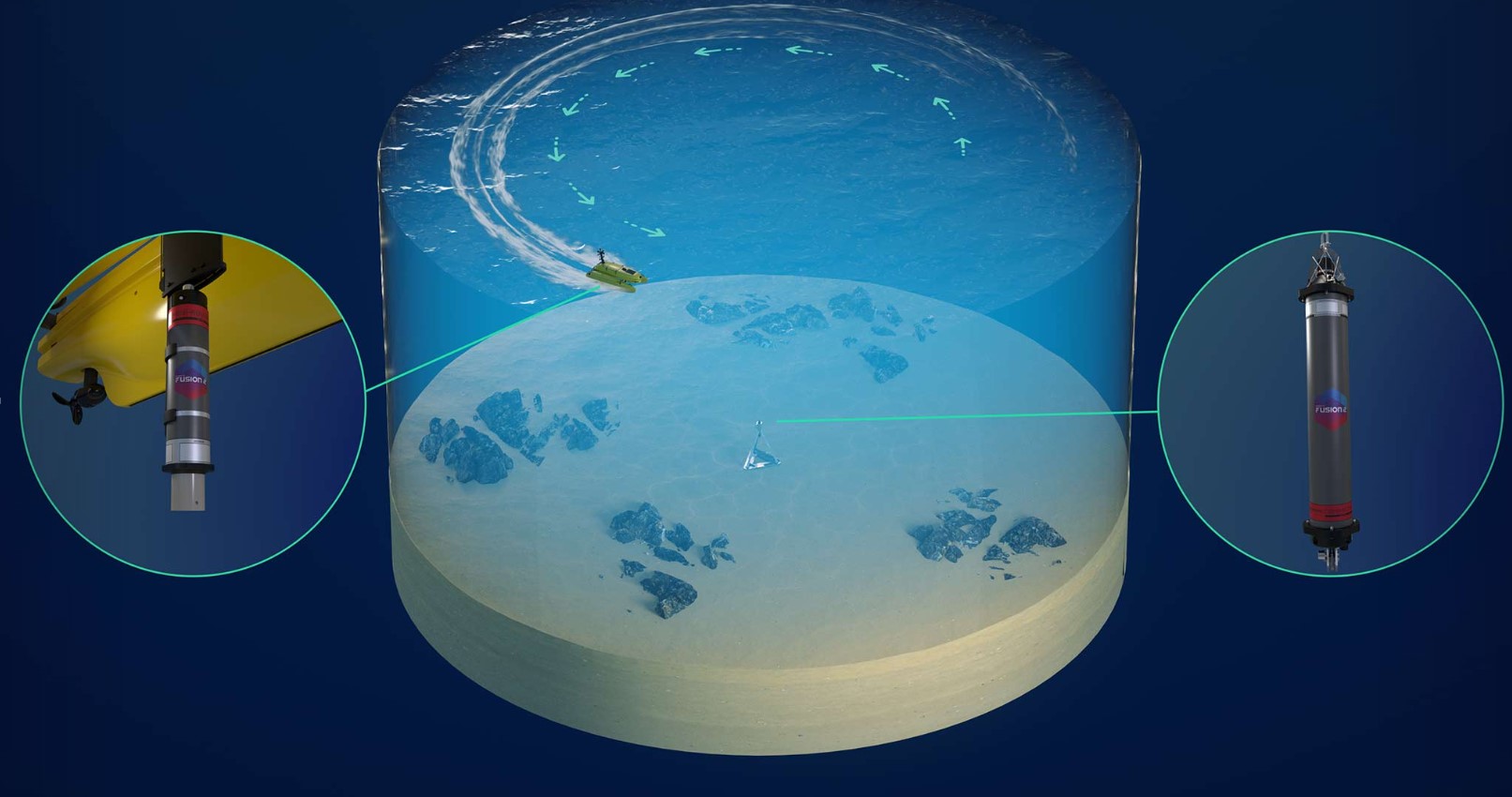

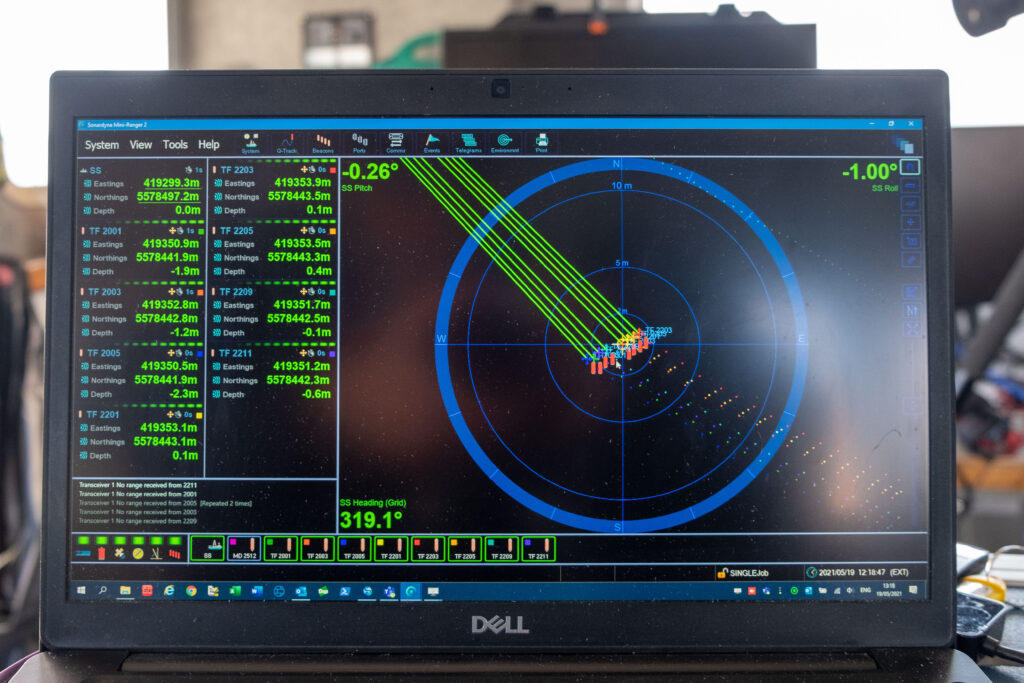

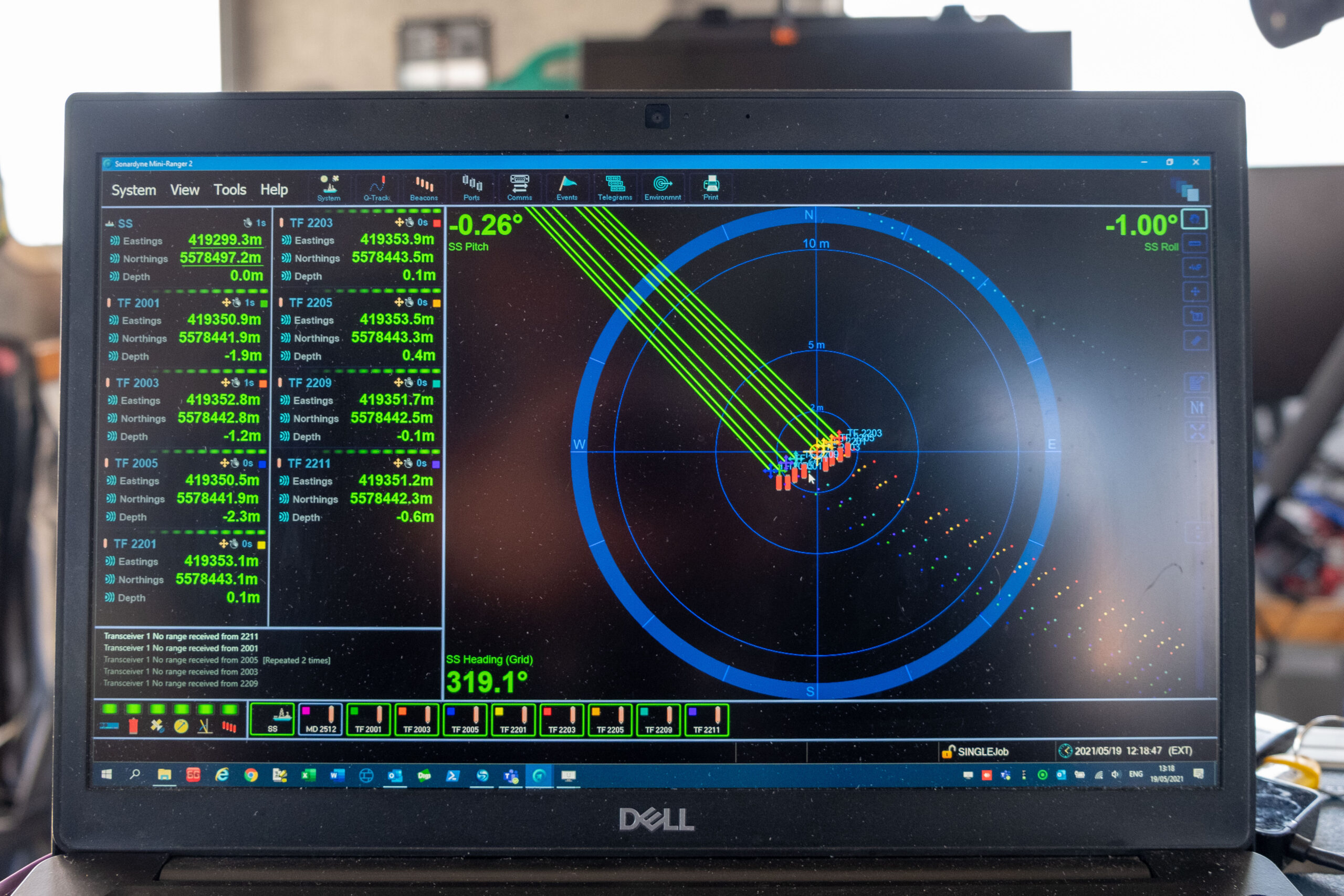

The fourth and final element is a surface gateway to enable communication between a shore-based monitoring office and the underwater systems. Such a gateway can be deployed from a fixed platform, from a moored buoy or from an uncrewed surface vessel (USV), many variants of which are now readily available in the market for over-the-horizon data harvesting missions.

We have a range of payloads suited specifically for use on operator’s USVs for their requirements. We also offer our own end-to-end data-harvesting service, when you just want the data without the worry about the interfaces involved in getting it.

Our system of systems approach to CCS was tested on the ETI project. Wideband acoustic communications between the underwater landers and a buoy on the surface was used to forward all data via satellite communications to a server. This type of set-up is well-proven and used globally on tsunami monitoring systems. Display and interpretation of the monitoring data can be simply integrated into a third-party system to allow non-expert users access via a web portal. From here they can see data visualizations and run reports.

The leak target was deployed in the North Sea, east of Bridlington. The NOC’s Autosub Long Range (ALR) was deployed from the small port at Bridlington and towed a short distance off the coast. After the ALR performed a series of tests to demonstrate safe navigation, the leak – a small CO2 leak – was turned ‘on’ with a flow rate of between 16 and 20 litres per minute of gas at depth, depending on the state of the tide.

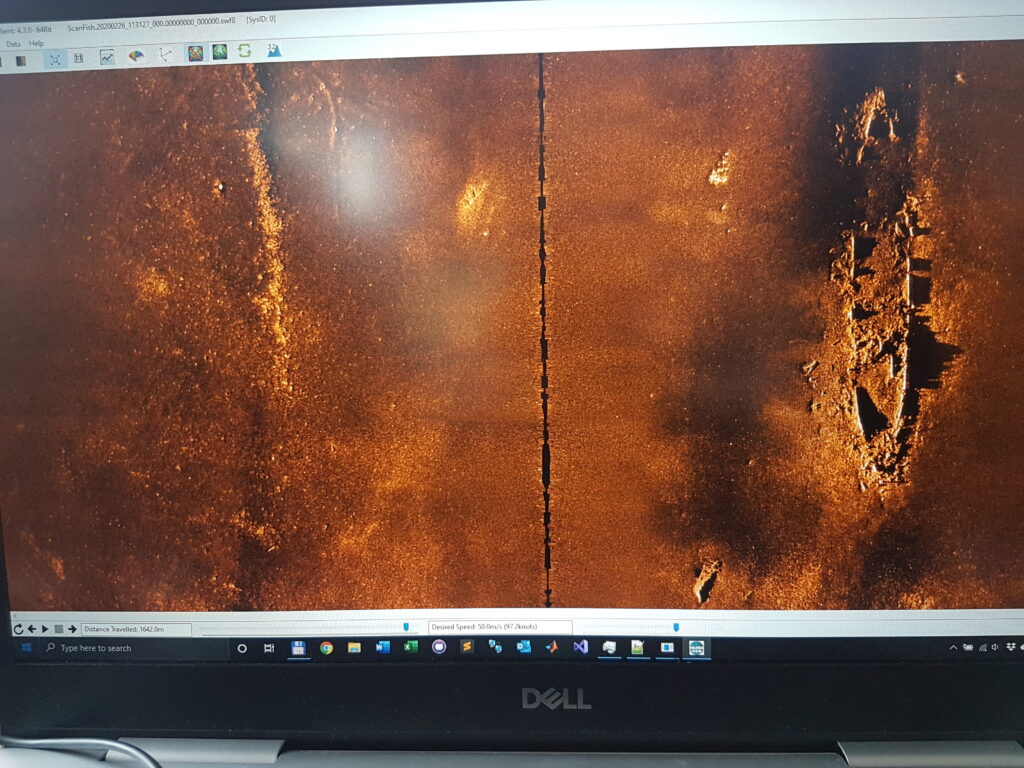

With the leak “on”, ALR performed a series of different wide-area and fine-area search patterns over five days to seek out the leak. The sensor hub on the vehicle processed in real-time a complex set of Solstice sonar, physical and chemical sensor data, into useful information.

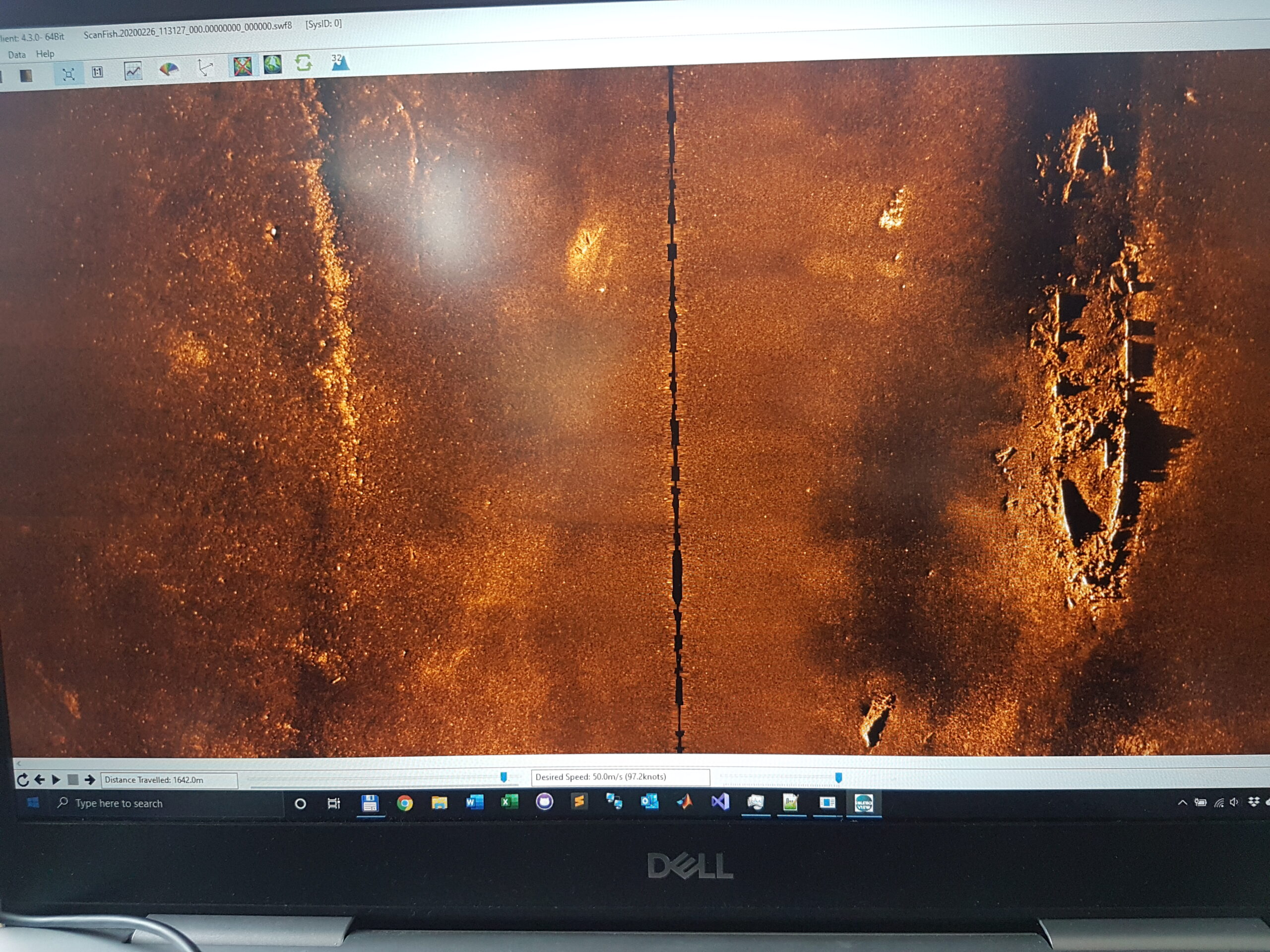

Automatic target recognition algorithms were used to identify any leaks or regions of interest. The system then scored these regions of interest and saved a small “snippet” of the sonar image data. At regular intervals throughout the survey, ALR would surface and send back data via satellite, including navigation data, chemical and physical sensor data and details of snippets of sonar data from detected leaks – an example of which can be seen below.

All of the uploaded data was simultaneously transferred to an internet server which allowed for presentation and interpretation using Fugro’s Metis software. This is an intuitive data delivery platform that allows metocean, vehicle navigation, chemical and sonar snippet data to be combined and displayed. This allowed data sharing across a wide team and supported operational decision making.

During the five days of testing, the ALR travelled a total of 270 km and could have surveyed 54 sq km of seabed in normal operation. However, for the purposes of the demonstration, a total of 16.1 sq km was actually surveyed. Throughout its mission, the ALR was remotely controlled from the shore, mostly from the NOC’s control room in Southampton.