The results

“This was a real first for us,” – Professor Larry Mayer, Director of the Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, University of New Hampshire.

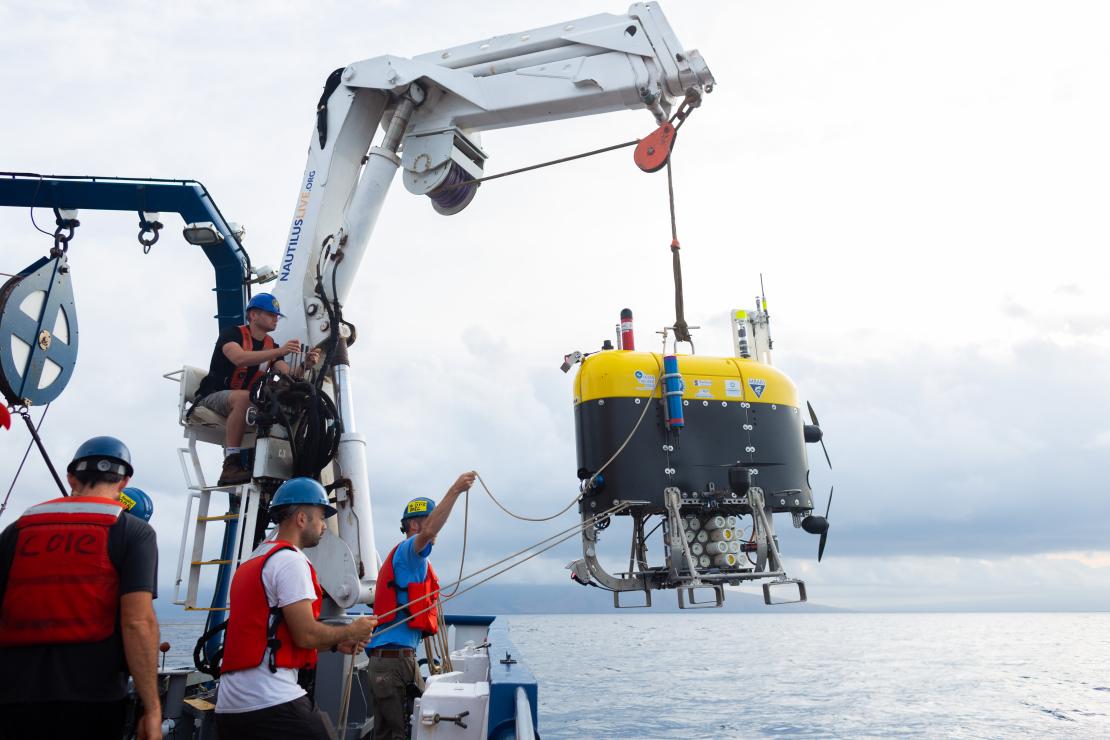

Over the course of the 16-day expedition near the island of Oahu, off Hawaii, the team tested and demonstrated operational capabilities. Over 30 dives were performed, totaling 210 hours in the water.

The team established a common control system, based on the robot operating system (ROS) for the vehicles and then set out, each time proving out more and more capabilities.

First, they had DriX track and communicate with Mesobot, using Mini-Ranger 2. Because the DriX has GNSS data at the surface, this meant it could position the Mesobot in the real-world and relay this data back to the RV Nautilus.

Next, they sent commands, via the DriX to Mesobot, from EV Nautilus to open and close its samplers, as well as to move up or down or to the right or left as well as change speed through the water column.

But then the most exciting thing happened, explains Professor Mayer:

“Mesobot is designed to sample layers in the water column. But it doesn’t know where they are. DriX has a sonar (EK-80) that could see those layers. So we could get DriX sonar data back on the ship and in real-time see what’s called the scattering layer of plankton and command the Mesobot to go to that layer to sample it.

“Because Drix is circling above, it can actually see the Mesobot in the layer. This was a whole new world. Normally, Mesobot is sampling blindly. We could now direct it into the layer, know it’s in the layer and see if its entrance causes the layer to scatter. All these were unknowns before.”

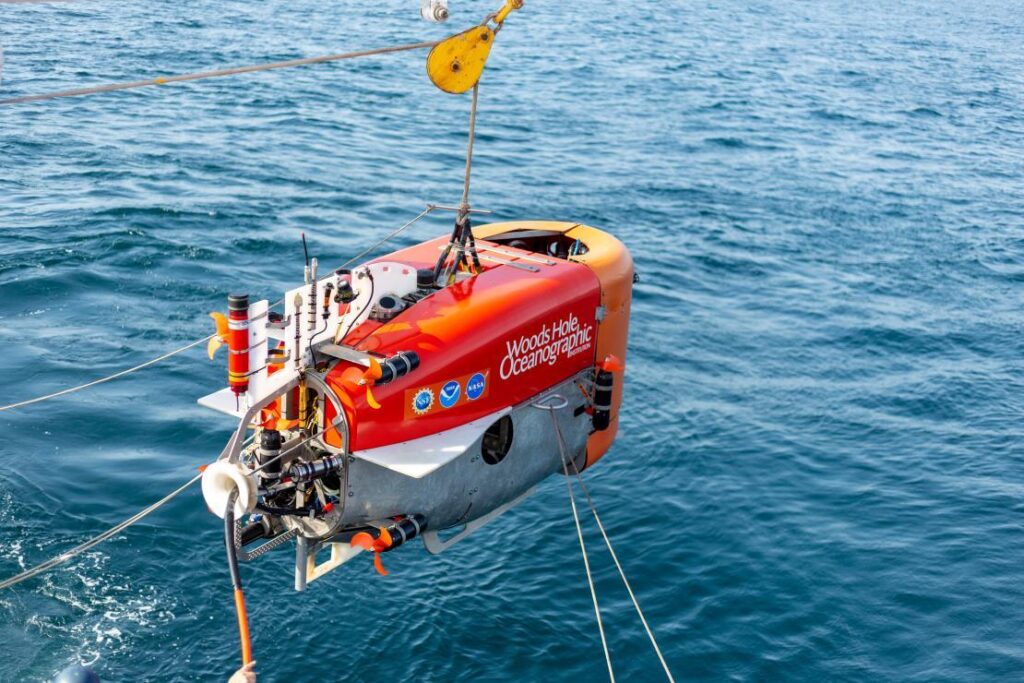

The team were then able to repeat these activities with NUI, including using DriX to map the seafloor east of Maui and then relay a mission to NUI for further investigation. In addition, CTD data, as well as snippets of imagery and bathymetry were transmitted acoustically up to the DriX, using Mini-Ranger 2, and then via the radio link back to the Nautilus.

“By the end of the cruise we were able to have both vehicles in the water with the DriX circulating above, communicating with each of the vehicles, giving each other situational awareness, and the mothership, it was off do its own thing. I couldn’t have asked for a more successful cruise,” says Larry.

“We are really opening up a new world of multi-vehicle operations. In the old days, we would schedule a cruise and just use the Mesobot or schedule a cruise and just the NUI or an ROV. Even if they would all fit on one ship at the same time, you only use one at a time, so the $60,000 a day would be clicking away and you’re only doing a single science operation.

“Now we can do 2-3 science operations, the efficiencies are tremendous and it allows us to explore the seafloor, water column and surface all at once.

“The Mini-Ranger 2 system gave us the broadest base of possibilities with having both the acoustic communications and the positioning, USBL and acoustic communications, from the same system and that combined set of capabilities was so important to us.

“The standardization and ease at which we were able to send messages across from our programmers made it easy to use. The cooperativeness and responsiveness of the team at Sonardyne was also really helpful. They didn’t see it as disruption, they saw the possibilities.”

The expedition was funded by NOAA Ocean Exploration via the Ocean Exploration Cooperative Institute.

For more information and to watch other videos from Nautilus, click here.