Floating offshore wind (FOW) offers a huge opportunity to tap deeper waters and often stronger and more consistent wind resources in them.

But it’s still early days for the sector, with significant technical and economic challenges to overcome in order to scale up. With the help of Will Brindley, Lead Naval Architect at Apollo Engineering, I’ve been exploring some of these challenges.

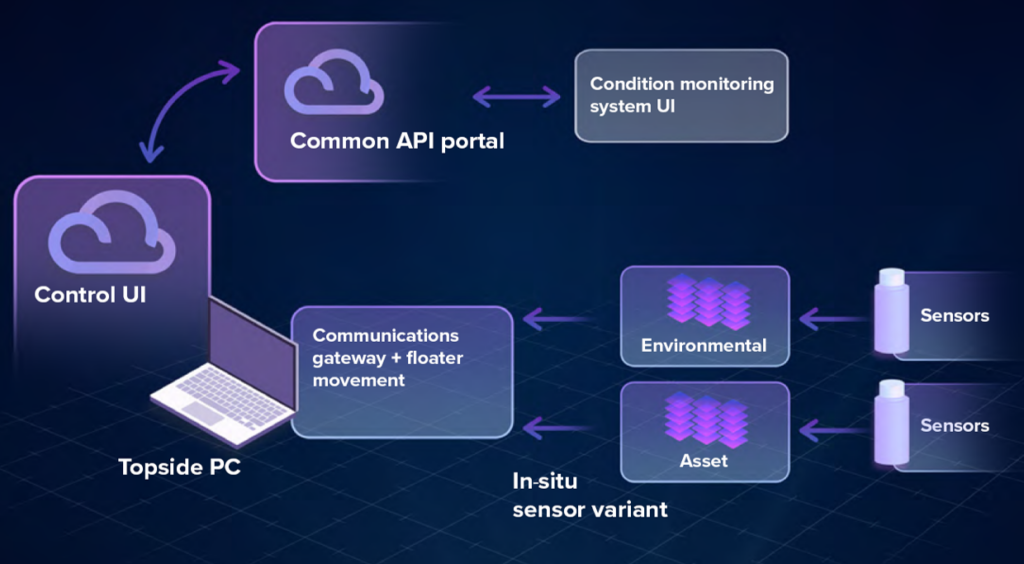

A key element in de-risking offshore wind in dynamic deepwater environments is the smart application of condition monitoring systems (CMS) and advanced data processing.

The current status: ramp-up and learning

The consensus across the industry is that FOW is currently ramping up, but the detailed engineering needed for gigawatt-scale projects (we’re talking 50 to 100 turbines) is just beginning.

This is why many are taking a phased approach—moving from smaller projects (like the 300 MW initial capacity for Equinor’s Celtic Sea project) to much larger 1.5 GW arrays—to test technologies and refine designs.

To an extent, we’re already seeing that. The industry has several small demonstrator projects in the water, providing essential early lessons. One of those is the need to focus as much on what went wrong as what went well.

A good example is the Kincardine project, near Aberdeen. This showed that while major component replacement is expensive (involving towing the unit to Rotterdam and back), successfully executing an in-field replacement was a big win in terms of sector learnings.

With intense pressure to reduce costs in this sector, the demonstrators are vital for these types of learning and we can also learn more from elsewhere.